Before you can reach a student’s head to learn, you need to reach their heart and earn their trust. Nearly a third of teenagers have experienced a trauma or are in a chronic state of trauma such as abuse, homelessness, foster care, hunger, bullying, substance abuse in the home and even human trafficking which makes focusing on academics especially difficult. And it’s likely that the trauma may be escalating as a result of being forced to shelter at home.

However, traumatized children who learn to thrive have someone in their life who encourages them and believes in their success. When school starts up again in the fall and instruction resumes (even if a hybrid model), students will need support in processing their emotions, learning to reconnect and catching up academically. Educators should strive to be that someone in students’ lives! Here are the keys to addressing student trauma:

Recognize your own feelings first. Just like on an airplane, you must put on your air mask before you can help others. That starts with acknowledging the grief and dislocation we are all experiencing. Take the self-care actions required so you can offer calm and empathy to students.

Create a sense of stability with flexibility. In times of change and uncertainty, consistency with flexibility is important. Some teachers are setting appointments with their students in the evening, so communication occurs regularly but on the student’s schedule f they must work or take care of children during the day to help support their family.

Just listen and validate honestly. Adults often want to “fix” things when a student just wants to be heard and supported. Instead of saying, “don’t feel bad” or “be strong,” acknowledging their feelings is the best way to earn trust and build a relationship.

Encourage students to ask for help. Be there when they reach out for support but know when you need to refer the student to another professional. A crisis may require involvement and collaboration with child/adult protective services, a mental health response team, law enforcement or community mental health agencies. Let students know that you will support them throughout the process, and then follow through.

Set appropriate expectations. Recognize each student’s abilities and circumstances or barriers before setting expectations. Be clear about what you expect and your confidence in the student’s ability to rise to the occasion. Notice and celebrate each success, no matter how small.

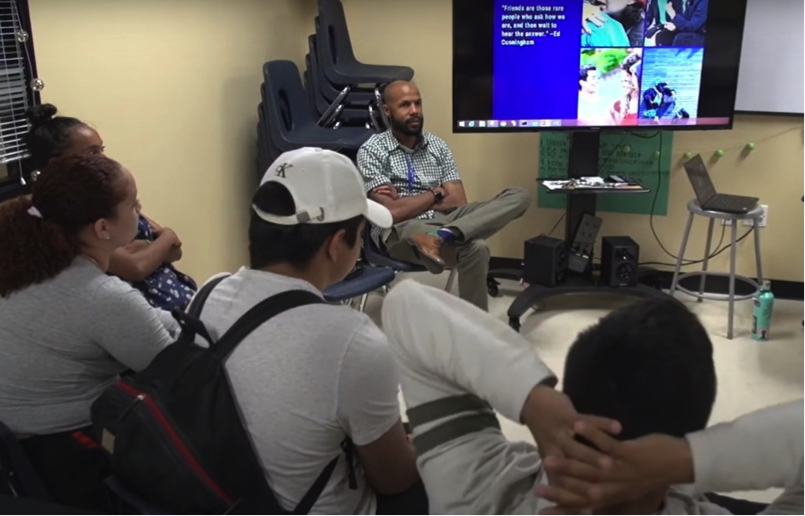

Remind them they are not alone. Everyone could probably use that kind of reassurance these days. Students are not alone in their struggles even though they may sometimes feel they are. Research shows that when adversity feels like a shared experience, we cope better – not only emotionally, but neurologically. Creating opportunities for peer support allows students to help each other, sharing their strength and giving them a sense of purpose.

A personalized approach is best. Students don’t all learn the same way, and they don’t deal with trauma the same way. Many of our high school students enroll reading at a fifth-grade level. And many others have never received counseling to deal with stress and grief. It is important to develop a program for the student that deals with their social-emotional concerns while tailoring curriculum to their instructional needs.

Just because we’re not in the same room as our students, we still need to support their social-emotional health and help them cope. School leaders who understand and integrate trauma-informed practices into teaching will find greater and long-term success for students, and – after all – isn’t that what it’s all about?